|

| This plaque is all that remains to memorialize the events at Fort Loyall. It is attached to the brick building once part of the Grand Trunk Railroad, now a bank at the foot of India Street |

The fort was rebuilt and renamed Fort Falmouth in 1742, located at the foot of India Street. An earthwork was built in 1755, called Lower Battery and re-armed for the French and Indian War. In 1776, Upper Battery was constructed at the upper end of Free Street, and Magazine Battery was built at Monument Square during the Revolutionary War. Nothing remains of any of these structures today.

The siege of Fort Loyall and the massacre of the two hundred souls who sought refuge there, caused the evacuation of people living in other settlements in Falmouth, and the abandonment of the garrisons in Scarborough, Spurwink and Purpoodock. Most people went south; some to Portsmouth, Salem and even Boston. Apparently temporary admission as citizens of these settlements was granted to these refugees, acknowledging the constant and unrelenting threat to their lives and well being that they had suffered. Some brave souls would attempt to return after a measure of peace was attained after 1699.

The historical record holds very few names of those who perished in the attack on Fort Loyall :

John Parker and his son James Parker Thomas Cloice Edward Crocker

George Bogwell Joseph Ramsdell Seth Brackett ( son of Anthony Brackett

Sr. who was killed on his farm in the battle of 1689.)

Lieut. Thaddeus Clarke, along with thirteen young men who went to secure the garrison near Munjoy Hill,

Capt. Robert Lawrence who was mortally wounded during the siege and died shortly after.

Here is an account of the Prisoners taken captive:

Lieut. Anthony Brackett, Jr. James Ross Peter Morrell James Alexander

Joshua Swanton (a boy) Samuel Souter Thomas Baker (a boy) George Gray

Sarah Davis ( a girl, and daughter of Lieut. Clark) and her sister, and

Capt. Silvanus (Sylvanus) Davis.

Two years later, in 1692, Col. Benjamin Church on his way to an expedition with Sir William Pitt, stopped at the site of Fort Loyall and found the remains of those victims of the massacre lying as they had been left; only bones bleached by the elements and ravished by birds. Some say, the soldiers, with Col. Church buried them somewhere on the site of the old fort. John T. Hull intimated that they may have taken them to the Old Burial Ground at Eastern Cemetery. We don't know. The large cannon was removed and taken to Boston.

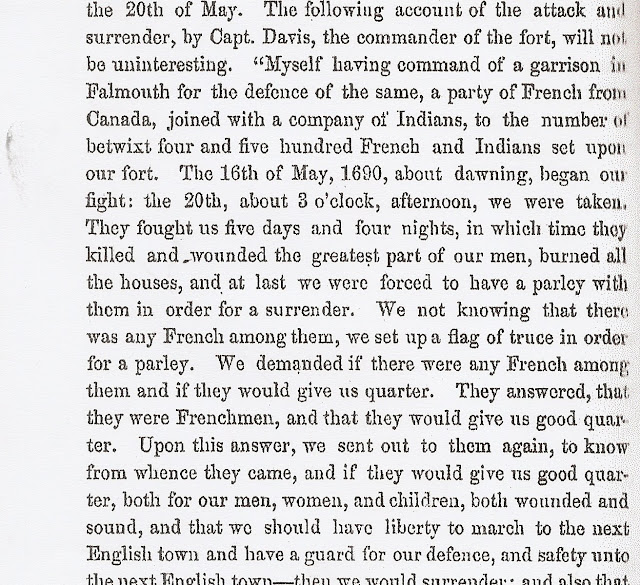

Capt. Sylvanus Davis was released after four months in exchange for a French captive taken by the English. Upon his return from captivity, he wrote a detailed and emotional account: "Declaration of Sylvanus Davis inhabitant of the town of Falmouth, in the Province of Maine, in New England, concerning the cruel, treacherous and barbarous management of a war against the English in the eastern parts of New England by the cruel Indians...." Mass. Hist. Soc. Col., 3rd ser., I(1825) 101 -12. For those who might want to read this, you can access it as an e book online.

Silvanus (Sylvanus) Davis was born c. 1635 and died on April 19, 1703 in Hull (Nantasket), Massachusetts. From 1659 on he owned land in Eastern Maine and on Casco Bay where he engaged in trade with the Indians and settlers, and also with the French.

In the early 1680's he moved from the Kennebec to Falmouth. He was an accomplished businessman and landowner, operator of both a sawmill and a grist-mill and a store while he carried on coastal trade He became a justice of the peace in 1686, and after his return from captivity, he was named a representative from Maine to the General Council. Later in the 1690's he moved to Massachusetts where he settled in Hull, still retaining some of his interests in Maine. He died there in 1703.

The 1690's were devastating for the English settlers throughout the Province of Maine, raids continued and those that could, left the vicinity in droves seeking safety wherever they could find it. The French and Indian allies had the upper-hand. While the Indians seemed like victors, according to William David Barry,

"their numbers were soon depleted in the epidemics that struck in 1695 and 1698."

Most settlements were totally destroyed, and thousands of refugees streamed into the Bay Colony. In 1694-1695, the General Council was so alarmed by the loss of its frontier buffer zone that it passed :An Act to Prevent the Deserting of the Frontiers."

Barry goes on to say:

While they might shed patriotic tears over conditions in Maine, they were not about to spend much to protect the inhabitants, and expected them to remain loyal defenders.

In 1697, a European peace treaty was signed, but it failed to establish an eastern border for Maine, and it was not until 1699 that local English and Indians came to peace terms. By then, fewer than 1,000 English were left in the district.

As a term of good faith, the Abenaki asked for a suitable place to trade and repair tools. Fort New Casco was erected and improved by 1700 by Col. William Wolfgang Romer. It's location was on a farm located on today's Route 88 across from the Pine Grove Cemetery.

Col. Romer was a military engineer who was engaged in drawing maps and designing plans of fortifications in New York and New England. He received his military training as a military engineer in the Dutch Army before becoming a member of the English Royal Engineers

Here is a description compiled by Pete Payette- @2014 American Forts Network

A large 70 - foot square earthwork and palisade fort, also known as Casco Fort, with an Officers' quarters, storehouse, and guardhouse, It was attacked by the French in 1703, rebuilt and enlarged in 1705 as an oblong square 250 feet long and 190 feet wide, with a supporting blockhouse at the shoreline. It was demolished by the Massachusetts government due to budget cuts. Some earthworks may still exist on private property (on Old Powderhouse Road?)Fort New Casco: (1698 - 1716) Falmouth Foreside

|

| This is a modern rendering of the 1705 cross - section of Fort Casco by Sisu458 - Own work, Created July 2014 |

On June 20, Governor Dudley convened a grand Council at Fort New Casco where the chiefs of the Norridgewock, Penobscot, Penacook, Ameriscogginaa and Pequakett tribes assembled. Great ceremonious rituals were held and two stone pillars named the 'two brothers', were erected to give testimony to the pledge of peace promised on both sides.

The frontier between New France and New England remained quiet until December. Governor Louis-Hector de Calliere and Vaudreuil, soon to be his successor, authorized the Abenaki to resume the border war. Although Governor Dudley received a warning from the Abenaki Chief Moxus about the impending aggression, Dudley brushed the warning aside, not believing the Abenaki would go to war again. Sadly, he was wrong.

This time, Indians raided the settlements at Spurwink and Purpooduck where the Jordan family had returned along with others. Twenty-two people were killed or captured at Spurwink ; the Jordan family. At Purpoodock, nine families were killed. At the area we now call Spring Point, twenty-five were killed and eight taken prisoners. Homes and garrisons were set on fire; the destruction of old Falmouth was almost complete.

Fort New Casco was commanded by Maj. John March. On August 10, 1703, the Indians under the leadership of Chief Moxus sent Major Church a message under the flag of truce that they had a very important communication to convey. Since the Indian party appeared to be unarmed, March agreed to meet with them taking only a few of his men as guards.

Major March was ambushed and two of his guards were killed. A garrison of ten soldiers commanded by Sgt. Hook rescued March and the Wabanaki withdrew. They skulked around the area setting fire to the surrounding houses. The rest of the Indian battalion in 200 war canoes arrived to complete the destruction of the village and to attack the fort in the same manner they had destroyed Fort Loyall in 1690. Fortunately, the "Province Galley", under the command of Capt. Cyprian Southack arrived on August 19th and relieved the siege, dispersing the Abenaki and some 500 French with its guns. The natives killed 25 English and took many others prisoner.

On September 26, 1703, Governor Dudley ordered three hundred men to march toward the main Indian stronghold located in present day Fryburg (Pigwacket). He also authorized bounties be paid for Indian scalps.

Maj. John March leading the 300 New Englanders chased the Wabanaki back to Pigwacket. March killed six and captured six. These were the first of New England's reprisals of the war.

In 1707, Major Samuel Moody became the Commander of Fort New Casco and remained so, until after peace finally returned with the Treaty of Portsmouth in 1713, and the fort at New Casco was ordered to be demolished in 1716. Major Moody would become a key figure in the resettlement of Falmouth (Portland.)

************************************************************

I will resume the story in late August after visiting with our wonderful grandchildren. Enjoy your summer!